The Construction Industry is once again facing a skills crisis. At a recent BBA webinar, Construction Skills Crisis – Past, Present and Future, Mark Harrison, Head of Equality, Diversion and Inclusion at the Chartered institute of Building (CIOB) explained that the Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) has calculated that the industry needs 217,000 new workers by 2025. Zooming in on specific skills, Mark noted that even before the tightening of the labour supply caused by the COVID pandemic, CITB were reporting that 40% of organisations were experiencing difficulties in recruiting suitably experienced project managers. Zooming out, in March of this year the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that the average number of construction sector vacancies per quarter stood at 38,000, the highest number since its records began in 2001.

A crisis 3 decades in the making?

Skills shortages are of course only one of several big challenges that the industry faces as it strains to ramp up activity following 2 years of COVID disruption. Materials shortages, spiralling energy prices and the wider impact of the war in Ukraine are all causing decision makers headaches. Unlike these challenges however, the industry’s skills crisis seems less a shock and more a long-term condition. Speaking at the same webinar, ex Institution of Civil Engineers Director of Policy Andrew Crudgington noted that he’d written his first report on the skills crisis back in 2008 and that many of the underlying issues raised still resonated today, including a lack of diversity, slow adoption of new technology and a heavy reliance on a ageing baby-boomer workforce.

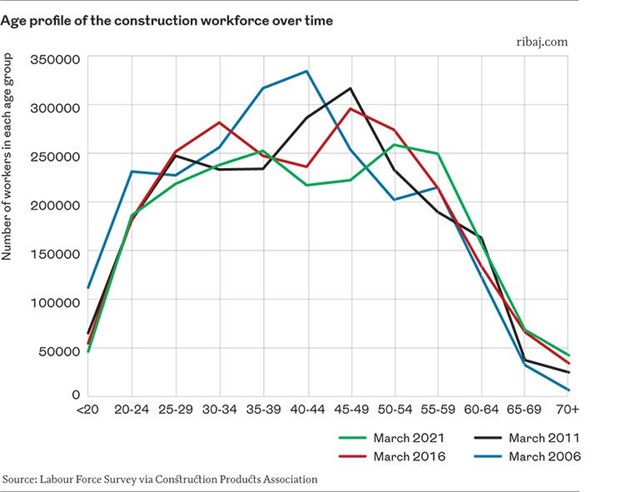

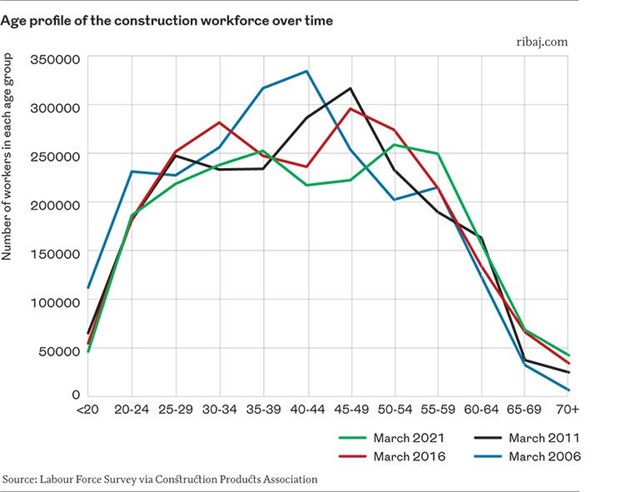

Illustrating this last point, Harrison noted that 35% of the current construction workforce are over 50 (with only 10% in the 19-24 bracket). In a 2021 article in the RIBA Journal, Brian Green traces this trend back to the 1980s, identifying a bulge in the construction workforce that is inexorably edging towards retirement.

He argues that this bulge relates to burst of heavy recruitment in the late 1980s when the economy was booming, which was followed by the depression of the early 1990s. When the economy picked up later in the decade and continued to grow through the 2000s, overseas workers increasingly picked up the slack – the proportion of non-UK born workers in the sector growing from 4% to 17% between 2000 and 2017.

The popularity of foreign workers relates to a point Crudgington raised at the webinar – UK contracting’s heavy reliance on self-employed workers. In a highly competitive, highly cyclical, low margin environment, contractors have understandably looked for a highly flexible workforce. Unfortunately, that can translate into a culture which tolerates a low investment in skills and repeated redundancies for individual workers, further damaging construction’s appeal to young people considering their career options.

Green argues that operating inside that culture it was natural for firms to tap into a ready supply of well-trained, battle-hardened overseas workers who were willing to move in and out of the UK market as it expands and contracts.

Post Brexit and Post Covid, that strategy is now much harder to pursue, even before we consider the missed opportunities it represents for Britain’s young people, so what should be done?

Can we solve the skills crisis by tacking construction’s diversity and productivity challenges?

The consensus of the webinar was that to really tackle the skills crisis we need to take a step back and address some of the big, structural weakness of the construction sector – or put more bluntly, shift its culture. Harrison drew attention to the sector’s poor record on diversity. Only 14% of the built environment workforce is female, dropping to 2% for roles on site. Similarly Black and Asian people account for only 6% of the workforce, set against 14% in the wider population. This all suggests an industry with an image and reputation problem that has failed to respond positively to a changing society. Similarly, its narrow demographics suggest that construction is consistently failing to communicate the sheer range of roles and careers it offers.

Culture change is long term project, that is going to need effective collaboration amongst businesses and organisations across the sector. As part of its contribution, BBA is holding another webinar on 28 June with Rebecca Lovelace Founder of Building People. Rebecca will be talking about how promote construction career opportunities to under-represented groups, as well as giving tips to businesses on how to collaborate with other players in the sector on practical issues such as sharing job vacancies, events and knowledge.

In addition to tackling the sector’s lack of diversity, Crudgington suggested that targeting the industry’s long running culture of accepting poor productivity was another indirect way to address its skills crisis. A shrinking pool of workers could be a catalyst for the industry to finally make serious investments in digitisation, modularisation and Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) more broadly – and again would signal that construction is an industry embracing technological change and the new people who come with it. BBA is committed to supporting the industry embrace MMC and examined its potential in a think piece published in March.

That paper made clear that MMC requires another cultural change, away from a demand to get spades in the ground as quickly as possible and towards getting more of a construction programme’s expenditure and activity to shift left into design and product development. It also demands a rigorous approach to quality in the factory and new capabilities in logistics and on-site assembly. The production process, including the role of a body such as BBA in certification, needs to be thought through, resourced, and the key players engaged early and integrated into a coherent production eco-system.

Diversity and productivity are both issues already high on the agenda of senior industry leaders and government so financial and moral support is available.

They also speak to the wider cultural change needed in the sector. If we can create an industry, that looks and feels like modern Britain and embraces technology and working practices commonplace in other industries we can begin to attract the people who can end our never-ending skills crisis.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related News

The Construction Industry is once again facing a skills crisis. At a recent BBA webinar, Construction Skills Crisis – Past, Present and Future, Mark Harrison, Head of Equality, Diversion and Inclusion at the Chartered institute of Building (CIOB) explained that the Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) has calculated that the industry needs 217,000 new workers by 2025. Zooming in on specific skills, Mark noted that even before the tightening of the labour supply caused by the COVID pandemic, CITB were reporting that 40% of organisations were experiencing difficulties in recruiting suitably experienced project managers. Zooming out, in March of this year the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that the average number of construction sector vacancies per quarter stood at 38,000, the highest number since its records began in 2001.

A crisis 3 decades in the making?

Skills shortages are of course only one of several big challenges that the industry faces as it strains to ramp up activity following 2 years of COVID disruption. Materials shortages, spiralling energy prices and the wider impact of the war in Ukraine are all causing decision makers headaches. Unlike these challenges however, the industry’s skills crisis seems less a shock and more a long-term condition. Speaking at the same webinar, ex Institution of Civil Engineers Director of Policy Andrew Crudgington noted that he’d written his first report on the skills crisis back in 2008 and that many of the underlying issues raised still resonated today, including a lack of diversity, slow adoption of new technology and a heavy reliance on a ageing baby-boomer workforce.

Illustrating this last point, Harrison noted that 35% of the current construction workforce are over 50 (with only 10% in the 19-24 bracket). In a 2021 article in the RIBA Journal, Brian Green traces this trend back to the 1980s, identifying a bulge in the construction workforce that is inexorably edging towards retirement.

He argues that this bulge relates to burst of heavy recruitment in the late 1980s when the economy was booming, which was followed by the depression of the early 1990s. When the economy picked up later in the decade and continued to grow through the 2000s, overseas workers increasingly picked up the slack – the proportion of non-UK born workers in the sector growing from 4% to 17% between 2000 and 2017.

The popularity of foreign workers relates to a point Crudgington raised at the webinar – UK contracting’s heavy reliance on self-employed workers. In a highly competitive, highly cyclical, low margin environment, contractors have understandably looked for a highly flexible workforce. Unfortunately, that can translate into a culture which tolerates a low investment in skills and repeated redundancies for individual workers, further damaging construction’s appeal to young people considering their career options.

Green argues that operating inside that culture it was natural for firms to tap into a ready supply of well-trained, battle-hardened overseas workers who were willing to move in and out of the UK market as it expands and contracts.

Post Brexit and Post Covid, that strategy is now much harder to pursue, even before we consider the missed opportunities it represents for Britain’s young people, so what should be done?

Can we solve the skills crisis by tacking construction’s diversity and productivity challenges?

The consensus of the webinar was that to really tackle the skills crisis we need to take a step back and address some of the big, structural weakness of the construction sector – or put more bluntly, shift its culture. Harrison drew attention to the sector’s poor record on diversity. Only 14% of the built environment workforce is female, dropping to 2% for roles on site. Similarly Black and Asian people account for only 6% of the workforce, set against 14% in the wider population. This all suggests an industry with an image and reputation problem that has failed to respond positively to a changing society. Similarly, its narrow demographics suggest that construction is consistently failing to communicate the sheer range of roles and careers it offers.

Culture change is long term project, that is going to need effective collaboration amongst businesses and organisations across the sector. As part of its contribution, BBA is holding another webinar on 28 June with Rebecca Lovelace Founder of Building People. Rebecca will be talking about how promote construction career opportunities to under-represented groups, as well as giving tips to businesses on how to collaborate with other players in the sector on practical issues such as sharing job vacancies, events and knowledge.

In addition to tackling the sector’s lack of diversity, Crudgington suggested that targeting the industry’s long running culture of accepting poor productivity was another indirect way to address its skills crisis. A shrinking pool of workers could be a catalyst for the industry to finally make serious investments in digitisation, modularisation and Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) more broadly – and again would signal that construction is an industry embracing technological change and the new people who come with it. BBA is committed to supporting the industry embrace MMC and examined its potential in a think piece published in March.

That paper made clear that MMC requires another cultural change, away from a demand to get spades in the ground as quickly as possible and towards getting more of a construction programme’s expenditure and activity to shift left into design and product development. It also demands a rigorous approach to quality in the factory and new capabilities in logistics and on-site assembly. The production process, including the role of a body such as BBA in certification, needs to be thought through, resourced, and the key players engaged early and integrated into a coherent production eco-system.

Diversity and productivity are both issues already high on the agenda of senior industry leaders and government so financial and moral support is available.

They also speak to the wider cultural change needed in the sector. If we can create an industry, that looks and feels like modern Britain and embraces technology and working practices commonplace in other industries we can begin to attract the people who can end our never-ending skills crisis.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related News

Get in touch

Please complete the form below and we will contact you as soon as possible.

To help us to respond to your inquiry as quickly as possible, we have put a handy list of our services below.